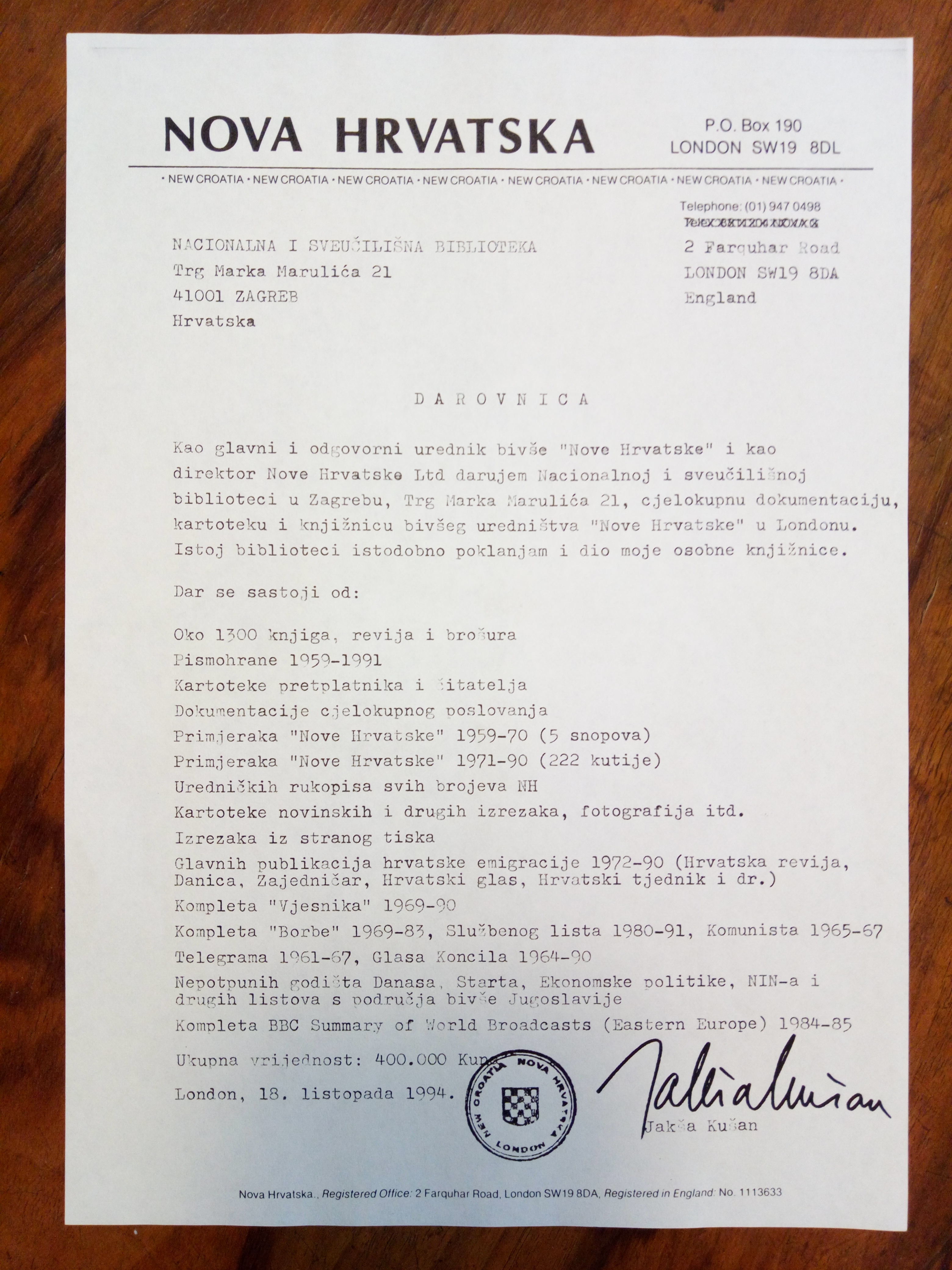

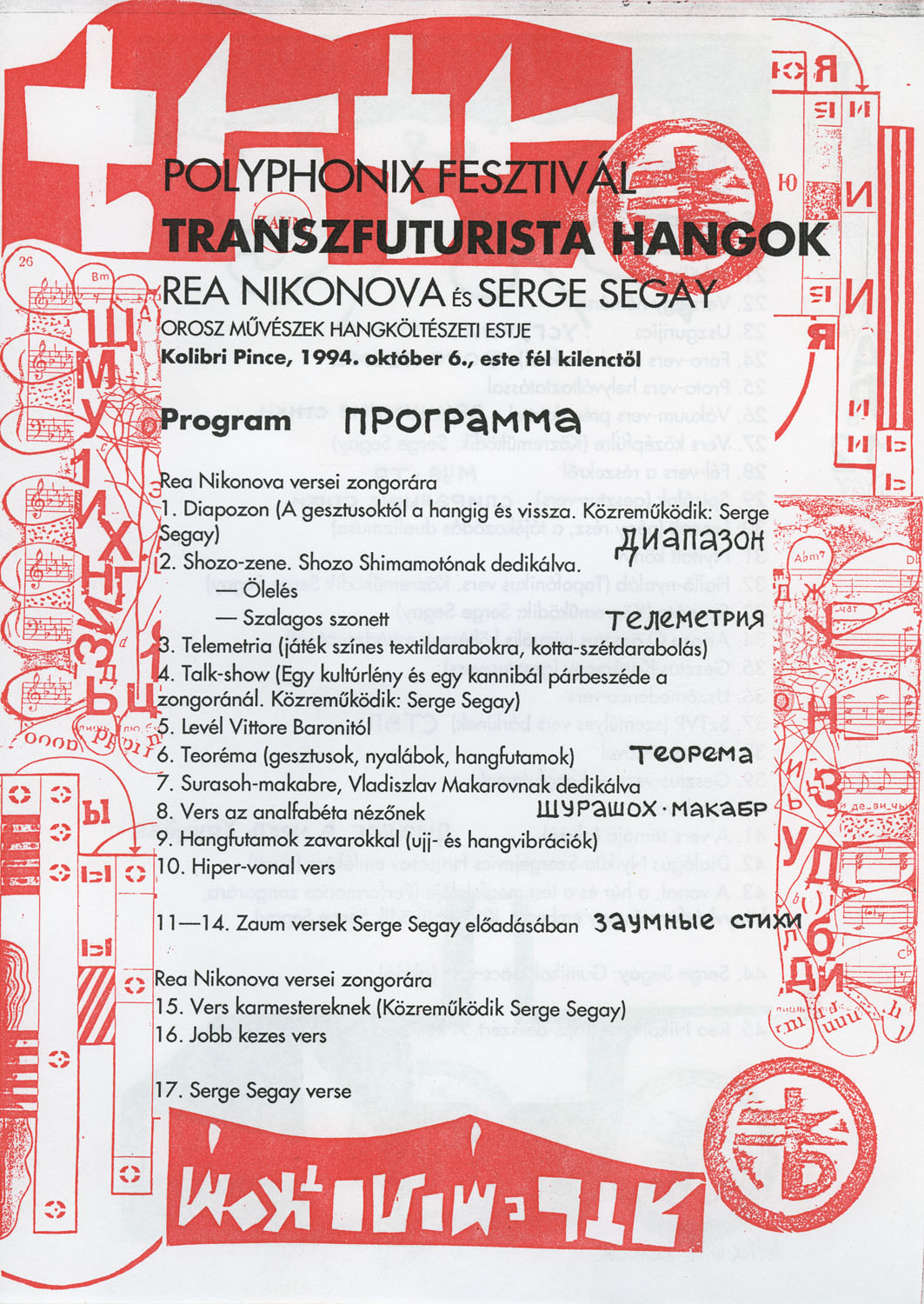

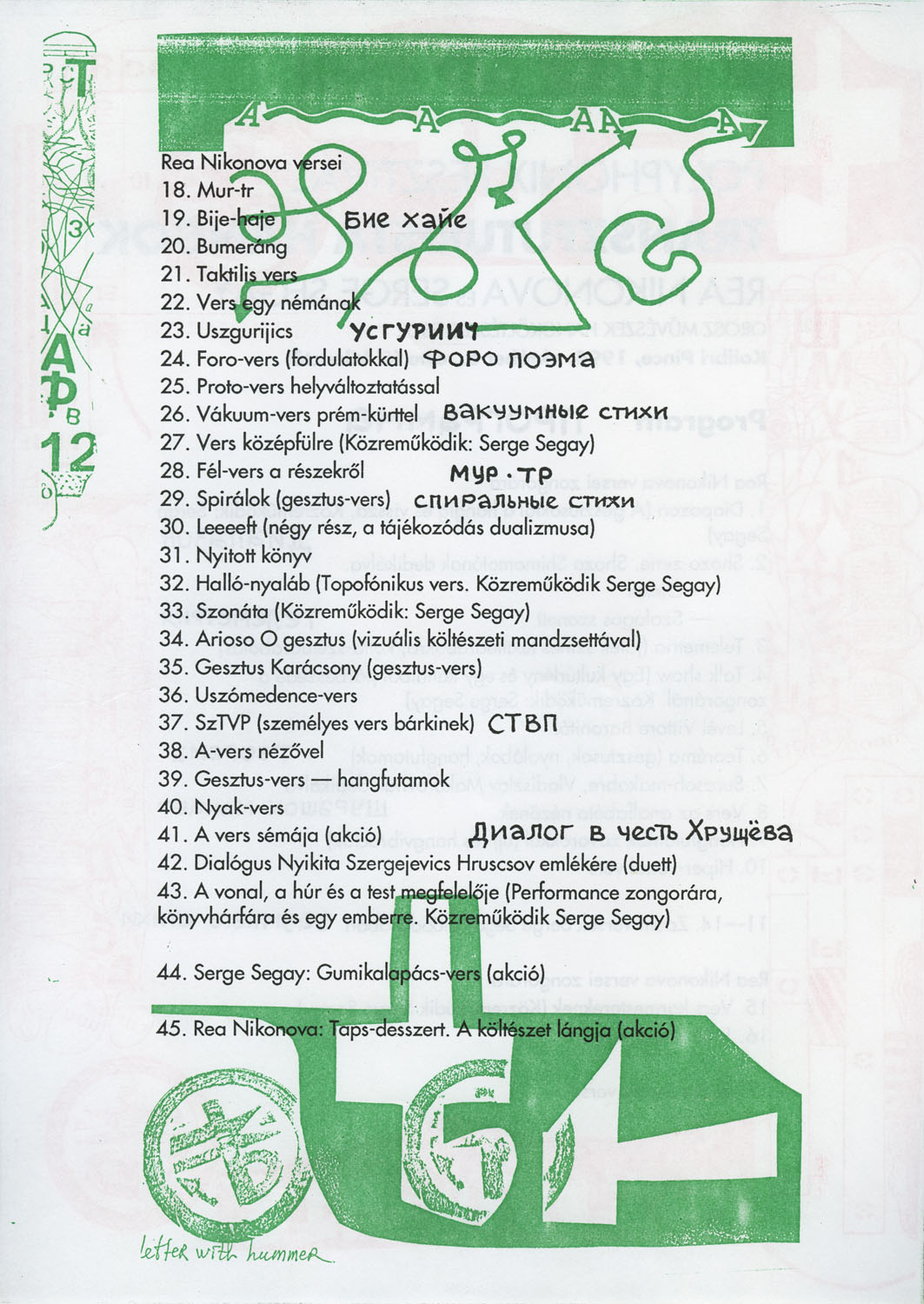

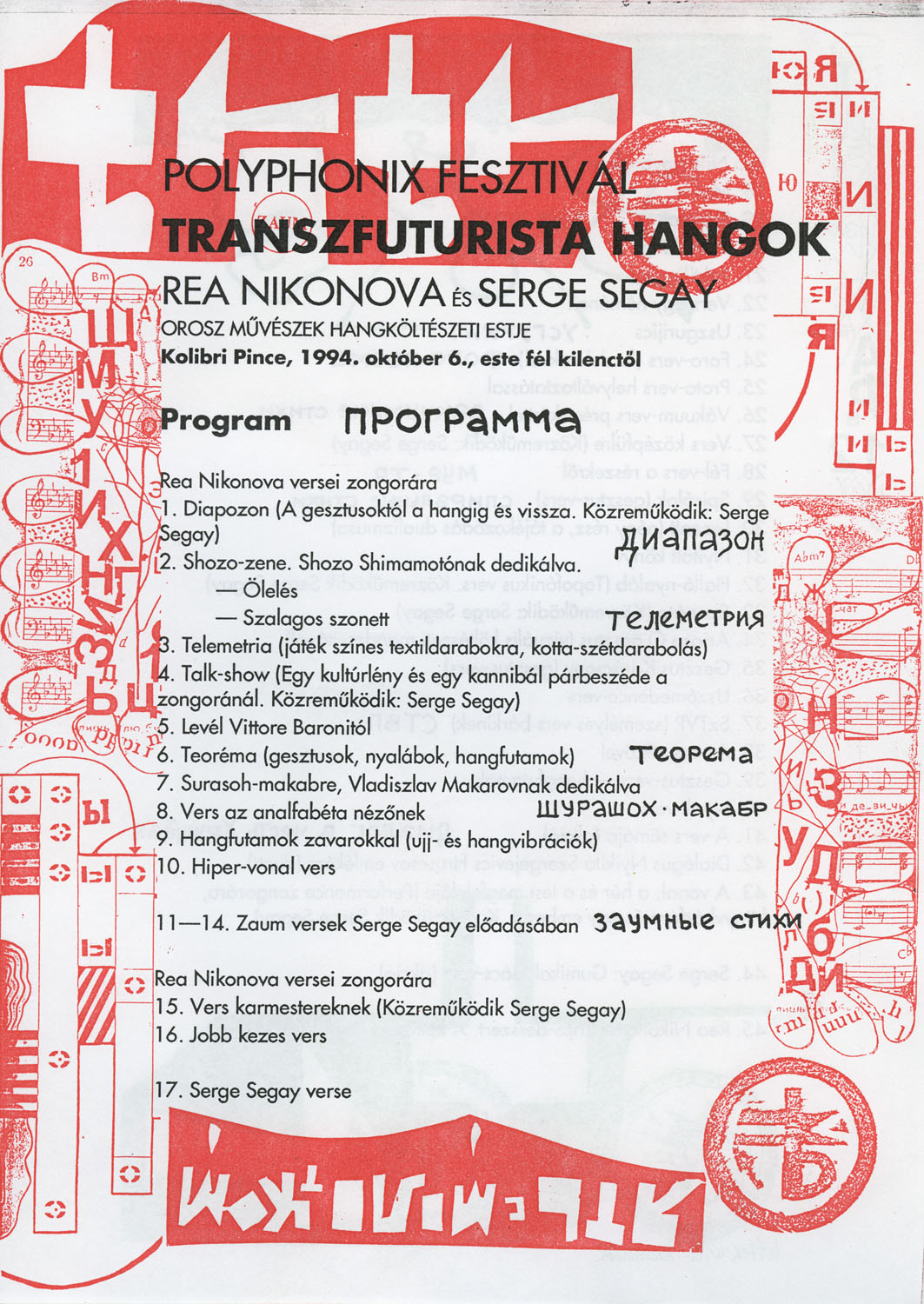

The 26th International Polyphonix Festival Budapest: the alternative poetry festival founded by Jean-Jacques Lebel in Paris is organized in a different city every year. After Paris, Naples, Rome, Marseille, and Brussels, Hungary hosted the event on two occasions. In 1988, the experimental artists came to Szeged, and in 1994 they came to Budapest. The Polyphonix Festival, in cooperation with Artpool, offered insights into the Russian experimental poetry scene: Rea Nikonova and Serge Segay presented their unique sound poetry show of gesture, vacuum, topophonic etc. abstract poems. Alongside the leading figures of the scene, such as Ernst Jandl, Julien Blaine, Timm Ulrichs, and Bernard Heidsieck, other artists appeared, such as Piotr Rypson, who gave a performance of Polish Futurist Sound Poetry.

The collection consists of artefacts about the 'Action of Light', established by Paulis Kļaviņš, which operated in the 1970s and 1980s. It aimed to support religious dissidents and human rights campaigners in Latvia, and to inform the public in the West about the real situation in Soviet Latvia.

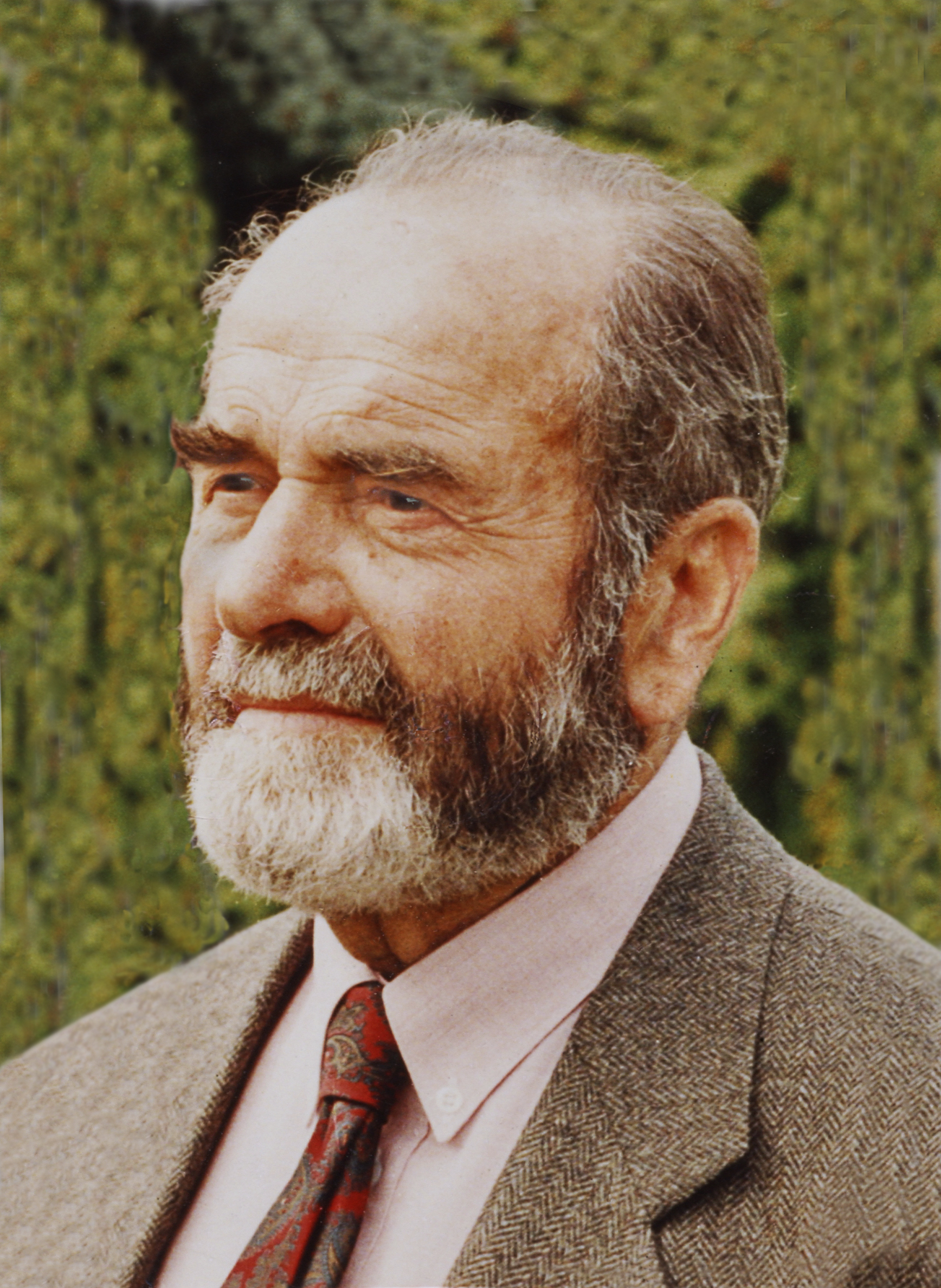

Ever since the 1990s, Adrian Marino had intended to donate his library and personal archive to a public institution to preserve it and make it accessible to the general public. According to Florina Ilis, the author considered a possible donation to the Library of the Romanian Academy as well as to the Museum of Romanian Literature in Bucharest. His decision to make the donation to the Central University Library of Cluj-Napoca (BCU Cluj-Napoca) was influenced by the manager of the institution at that time, the historian Prof. Doru Radosav. He convinced Marino that the institution he was running was the most suitable to preserve and valorise his collection. On 31 March 1994, Adrian Marino signed before a notary public the donation deed through which his personal archive and library were to be transferred gradually to the custody of BCU Cluj-Napoca. In the second part of the 1990s, most of the files in his personal archive were delivered to BCU Cluj, and after his death in March 2005, his library was also transferred to this institution. Florina Ilis, employee of BCU Cluj-Napoca, was in charge of archiving the Marino Collection, a process which took place under the author’s guidance. The room in which the collection was deposited is intended especially for doctoral students and young researcher. Given its size and cultural value, we consider the Marino Collection to be one of the most important private collections received by BCU Cluj-Napoca.

From the outset, one of the main aims and preferred profiles of the Soros Foundation Hungary (HSF), was to provide support for contemporary Hungarian literature through the numerous grants and prizes offered for writers and literary scholars as well as the largescale system of support for book publishers, periodicals, and libraries following 1989–1990. The jubilary anthology of works by 58 writers, which enjoyed the support of the Foundation, was launched to mark the 10th anniversary in order to represent the versatile values of this literary heritage, with a forward by novelist Miklós Mészöly and the title by Péter Esterházy: Ha minden jól megy / If Everything Goes Well on Its Way. It was published in 1994, more or less at the halftime of Soros Foundation Hungary’s support for Hungarian literature, by a new Budapest scholarly publisher, the Balassi Publishing House.

In fact, this special project of literary grants and other forms of support was originally intended to be but a modest experiment to determine whether an alternative patronage system based on private donations by George Soros could work more or less independently outside the prevailing system of communist cultural policy. The call for grant applications was announced, and in early 1985, an advisory board was formed of four devoted middle-aged experts: Miklós Almási, Mátyás Domokos, Ottó Orbán, and Endre Török, chaired by a widely respected senior poet and essayist, István Vas. It was quite clear from the outset that the process of selecting the grantees required considerable attention to detail, and results could only be achieved step by step. Therefore, most of the successful applicants were recruited from among authors who had not been banned or supported by the regime, but rather had simply been tolerated. Dissident writers, who by that time published their works mostly in samizdats, or writers who were more radically critical (such as intransigent poet György Petri) were repeatedly denied support by the party through the co-chairman of Soros Foundation Hungary, an apparatchik who represented the Hungarian Academy of Science. Still, some dissidents were able to secure support later, such as György Berkovits, Zsolt Csalog, János Kenedi, and Sándor Radnóti.

1989 and 1990 brought major changes. The advisory board was renewed and divided into two separate juries: one responsible for belle lettres, another for literary scientific support. Instead of grants, a system of literary prizes was established named after Hungarian nineteenth-century and twentieth-century classic authors, like Endre Ady, Lajos Kassák, Dezső Kosztolányi, Gyula Krúdy, Imre Madách, Sándor Weöres, etc. Furthermore, a set of new projects was launched to provide direct support for literary publishers, periodicals, and libraries throughout the country. During the first ten years (i.e. up until 1994) of the Soros literary patronage program, altogether 330 grantees and 50 prize-winners were given support. Most of them were original, middle-aged talents, including several Hungarian poets and novelists from Romania, Yugoslavia, and Czechoslovakia, such as Lajos Grendel, Elemér Horváth, István Szilágyi, Ottó Tolnai, János Székely, Árpád Tőzsér, and László Végel.

Pop-Săileanu, Aristina, interviu de Liana Petrescu, 1994. Transcript, Memorialul Sighet - Colecția de Istorie Orală

Pop-Săileanu, Aristina, interviu de Liana Petrescu, 1994. Transcript, Memorialul Sighet - Colecția de Istorie Orală

Among the first few hundred recordings in the oral history archive of the Sighet Memorial, Aristina Săileanu-Pop’s testimony stands out due to the fact that it tells of the personal experience of one of the most striking representatives of the organised resistance in the mountains of Maramures after the seizure of power by the communist regime. The recording of this testimony is number 254 in the archive. The audio document comprises some three hours of recording and is in digital format. The archived interview was taken by Liana Petrescu, and is accompanied by a file entry on the interviewee which summarises the content and provides Aristina Săileanu-Pop’s biographical details. An edited transcript of the recording was reproduced in the volume Să trăiască partizanii până vin americanii! Povestiri din munţi, din închisoare şi din libertate (Long live the partisans till the Americans come! Recollections from the mountains, from prison, and from freedom) published by the Civic Academy Foundation publishing house in 2008. The interview includes accounts not only of the personal experiences of Aristina Săileanu-Pop, but also of similar experiences of other members of her family and other partisans involved in the resistance movement in the mountains of Maramureş. These either did not survive the prison experience that followed their capture by the Securitate troops or they were older and passed away before the fall of communism, without having the possibility of narrating the traumatic experiences they had been forced to undergo. Aristina Săileanu-Pop considers that it is her duty to preserve their memory too.

As regards the significance of her own confrontational experience, Aristina Săileanu-Pop believes that her personal victory over the communist experiment in the history of Romania was due to her refusal to give up Christian moral principles: “It was a victory for all those who kept normality. I consider myself one of them. A peasant, I was and I remain a normal person; neither I nor my relatives had any inferiority complexes. My father was often in the company of important people of the time, although he was a forester. When Constantin Brătianu handed over the land, forests and all, to the people of Lăpuş, my father invited him to dinner and then they danced the Unification Hora together. We didn’t suffer any inferiority complexes. We always thought it was to the benefit of the country for there to be as many intellectuals as possible. From our village a host of boys and girls left for high school, because the peasant wanted his child to get book learning. Now, this “class” hatred was something incomprehensible; it exploited all the worst in people. It destroyed so many destinies; it left behind it suffering and death; it wanted to separate people from God. To take away their faith, hope, and love. The experiment you speak of ended with an ocean of injustices. I am just a drop in that ocean.”

In the preface to the volume mentioned above, Romulus Rusan responds to this story that is so moving in its simplicity, and offers a very beautiful portrait of a strong character, worthy to be taken as a life’s model: “Aristina Pop passes through the most terrible sufferings, but always finds a protective hand to defend her. She is the person who knows how to make herself loved because she is incapable of hate. She disarms the investigators by her ingenuousness, the women guards by the fact that she could be their child, the doctors by the altruism of her youth. […] She does not lose her faith, refuses resignation, continues to hope. After she comes out of prison, when the Securitate try to use her, she tells them they would do better to send her back behind bars. She gets married ‘at first sight’ to a young man, Nicolae Săileanu, who had been in the same prison as her and who had fallen in love with her without knowing what she looked like, just from hearing her story. [...] How did such a character manage to make herself loved in a world of hate, of class struggle? The secret is Aristina’s alone, and consists, beyond doubt, in her innate knowledge of how to remain normal in a world of abnormality.”

The last issue of the CADDY bulletin contained a recapitulation of the work of both the CADDY and the bulletin itself. Although the last issue appeared in November 1992, sometime later, at the beginning of March 1994, it was announced that the work of the CADDY had ended, which included the publication of the bulletin. This all happened against the backdrop of the definitive disintegration of the Yugoslav state and the war in its former territory. Such a turn of events signalled a defeat for the ideals championed by Mihajlo Mihajlov and Rusko Matulić as the main leaders of the project, who believed in the possibility of maintaining Yugoslavia in a democratized form.

Most likely, this epilogue forced Mihajlov and Matulić to forsake their work around the CADDY and the bulletin. On the other hand, there was no single-party dictatorship in the republics of the former Yugoslavia, and the public was no longer strictly controlled as it was in the preceding period. During the 1990s, the first multiparty elections were held in all of the Yugoslav republics. However, in his final message to readers, Mihajlov pointed out the pioneering role of the CADDY in informing the Western public about the status of political freedoms and human rights in Yugoslavia, and in presenting the fate of each dissident. He also stressed that CADDY was quoted in over 20 books and 60 magazines and newspapers throughout the Western world. (Rusko Matulic Papers, box 4).

1990 (1994), (set of three books in a paper case). The bookwork focuses on the topic “Freedom/Oppression: Central European Artists in Response.” In 1989, when the Soviet Union lost control over the Eastern Bloc countries, in the Visual Art Research Studio of Arizona State University three Hungarian artists selected with the help of Artpool began to work on the project. Peter Forgács, György Galántai, and poet György Petri were invited to Arizona to collaborate with the staff of the Studios, and as the fruit of their labors, the bookwork was produced in 1994 in 225 numbered and signed copies.

The collection is held in the Lithuanian Special Archive. The archive was arranged to manage a special collection of material that consists mostly of Soviet Lithuanian KGB, Communist Party and Interior Ministry documents. Documents from these former institutions are recognised by the Lithuanian government as material of special status, and they are separated from other government archive documents. The Lithuanian Special Archive is a governmental institution that supervises, keeps, stores and initiates legislation regarding this special group of documents. The collection is part of this group. It holds various documents about Lithuania’s anti-Soviet armed resistance in 1944-1953. While the partisan movement is related more to the resistance rather than to cultural opposition issues, the collection includes creative work by partisans, such as poetry, drawings, works of art, cards, and other items. The existence of this kind of work demonstrates the phenomenon of Lithuania’s anti-Soviet resistance and cultural opposition which was not limited only to armed rebellion. Partly because of this, the partisan resistance has a deep influence today on the Lithuanian historical memory.