Vjesnik Newspaper Documentation is an archival collection created in the Vjesnik newspaper publishing enterprise from 1964 to 2006. It includes about twelve million press clippings, organized into six thousand topics and sixty thousand dossiers on public persons. Inter alia, it documents various forms of cultural opposition in the former Yugoslavia, but also in other communist countries in Europe and worldwide.

The sentence in the case of Nicolae Dragoș and his oppositional group was pronounced on 19 September 1964, following a final round of testimonies that the main defendant and his associates provided in court. The main defendants, Nicolae Dragoș and Nikolai Tarnavskii, were accused of “common anti-Soviet views” that prompted them to “create an underground organisation on whose behalf they [intended] to undertake agitation and propaganda activities with the aim of undermining and weakening Soviet power.” Judging by the summary of their actions in the text of the sentence, the two main protagonists and initiators of this group started to discuss concrete plans for spreading their message in the summer of 1962, when the plan to set up a clandestine printing press emerged. It is interesting to note that initially Dragoș planned to print the leaflets a bit later, in 1965 or 1966, after a longer period of preparation, but, “due to the difficulties of provisioning the population with foodstuffs, which emerged throughout the country because of a poor harvest, decided to do this in 1964.” This passage is especially revealing both as a rare admission of real economic problems (albeit in a secret document) and as an indication of a direct stimulus that prompted Dragoș and his collaborators to act when they did. The sentence also carefully summarises the main stages of the organisation’s activity, i.e., the collecting of addresses to which the leaflets were to be sent in several Soviet cities (including Lviv, Minsk, Kiev, Leningrad, Dnepropetrovsk, Rostov-on-Don, Kharkiv, Odessa, Chișinău, etc.) and the recruitment of new members who were entrusted with practical tasks. The sentence also clarifies the structure of the organisation’s core, which seems to have included an inner circle (composed of Dragoș, Tarnavskii, and Cherdyntsev) and an “outer ring” consisting of the other three defendants (Postolachi, Cemârtan and Cucereanu), all of them students at the Institute of Fine Arts whom Dragoș recruited through his brother, Vladimir. The text of the sentence also provides a chronological narrative of the printing and dissemination of the 1,300 leaflets produced by Dragoș and Tarnavskii between February and 15 April 1964. Dragoș’s situation was aggravated by the accusation that, while trying to recruit new members, he “attempted to create the impression that a widespread clandestine organisation purportedly existed,” thus “camouflaging his own role in its founding and in the producing of the anti-Soviet leaflets.” Dragoș and Cherdyntsev were also accused of writing a letter to the First Secretary of the CPSU, Khrushchev, in which they purportedly “articulated calumnies concerning the policy of the communist party, against Soviet democracy” and “threatened the CPSU, on behalf of the clandestine organisation that, if repressive measures were to be applied against the DUS, the latter’s members would respond by similar measures, up to and including organising strikes and public demonstrations.” Several copies of this letter were later confiscated by the KGB from the defendants’ apartments. Given the fact that over 850 leaflets were distributed in various Soviet cities, it is obvious that the Soviet authorities were worried about the potential impact of the organisation and about the extent of its informal network. Despite Dragoș’s insistence that he did not pursue the goal of “undermining Soviet power,” all the defendants were found guilty of distributing anti-Soviet leaflets in which they propagated “vicious calumnies concerning the policy of the party and of the Soviet government, the Soviet state and social order, and the living conditions of the workers in the USSR.” The group was accused of extrapolating from certain particular problematic issues in the economic sphere and the “temporary difficulties” faced by the regime in order to recruit “politically unstable” citizens, mainly from student circles, and to manipulate them so as to achieve the organisation’s “hostile goals.” Consequently, Nicolae Dragoş and Nicolae Tarnavskii were sentenced to seven years in a high security labour camp. Ivan Cherdyntsev and Vasile Postolachi were sentenced to six years in a high security labour camp, while Sergiu Cemârtan and Nicolae Cucereanu received a five-year prison term, under similar conditions. Additionally, Dragoş and Tarnavskii were condemned to three years of prison according to article 81, paragraph 2, of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR, for stealing the printing equipment from Tatarbunar. The sentence also included a provision relating to the confiscation of the property belonging to the main defendants. As the latter possessed no significant property, the confiscation measure was suspended. The sentence was annulled in February 1989 by a special decision of the Supreme Court of the Moldavian SSR, by which Dragoş and his co-accused were rehabilitated. However, the additional three-year prison term for stealing the printing equipment was left standing by this court decision. The case of the Democratic Union of Socialists, closely linked to the context of the “thaw,” is emblematic for its openly political focus, its supra-national scope, and the possible parallels to much more significant similar cases in the Soviet Bloc. It is also interesting because of its “transitional” character. Although a direct product of Krushchev’s era, it also foreshadowed some of the topics that would be salient in the “dissident” movement on the Soviet periphery in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

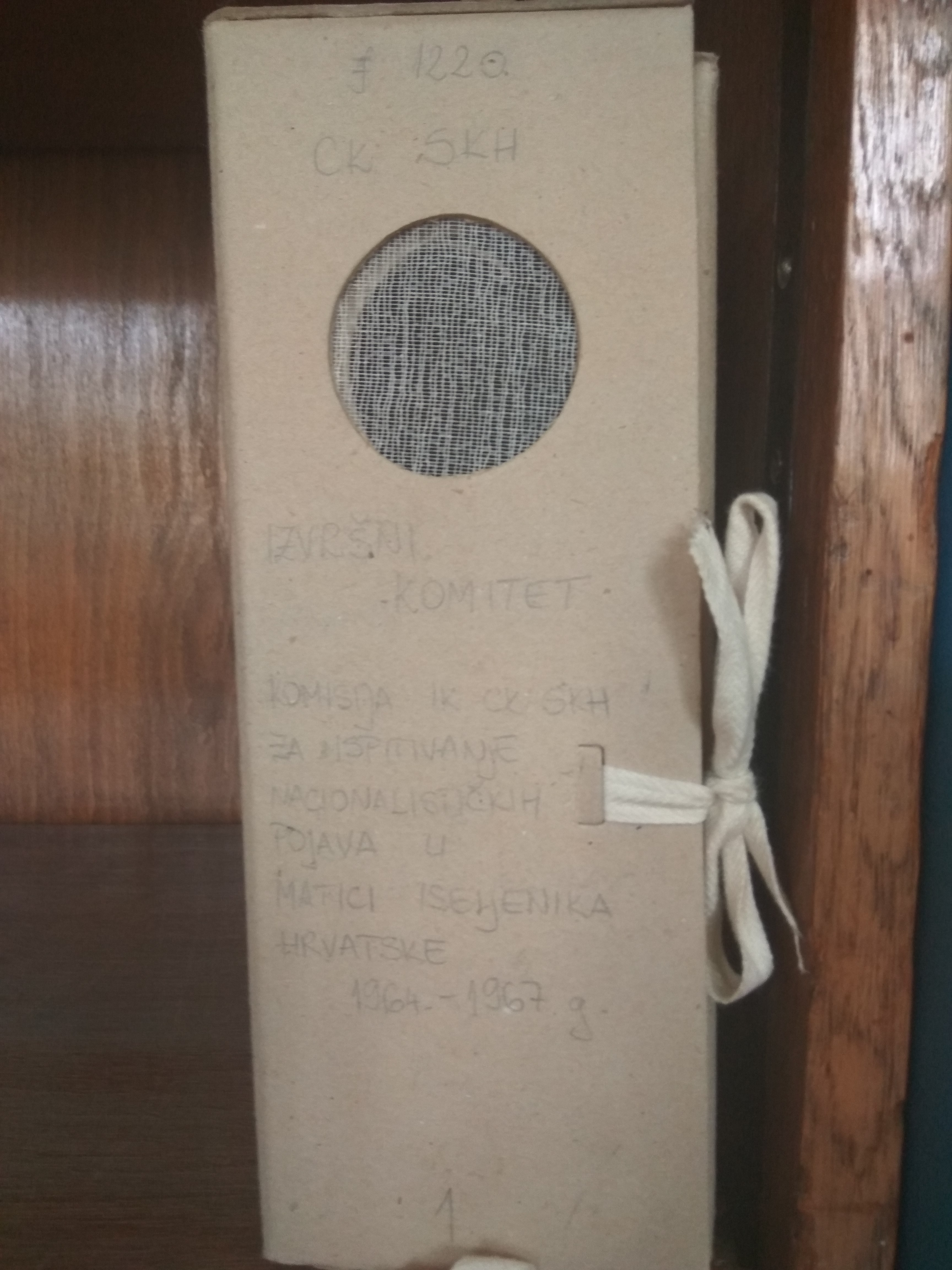

This thematic collection documents the work of the Commission for the Examination of Nationalist Phenomena in the Emigrant Foundation of Croatia (EFC) of Executive Council of the Central Committee of the League of Communists of Croatia (EC CC LCC), in the period from 1964 to 1967. The commission was established solely to monitor the activities of the EFC's president, Većeslav Holjevac, and some of his associates, who were considered as opposition figures and nationalists. The collection contains documents that explicitly cite examples of oppositional activities in the EFC which testify to the role of the EFC leadership in opposition in the field of culture pertaining to Croatian emigrant communities, as well as the role of CC LCC in their condemnation.

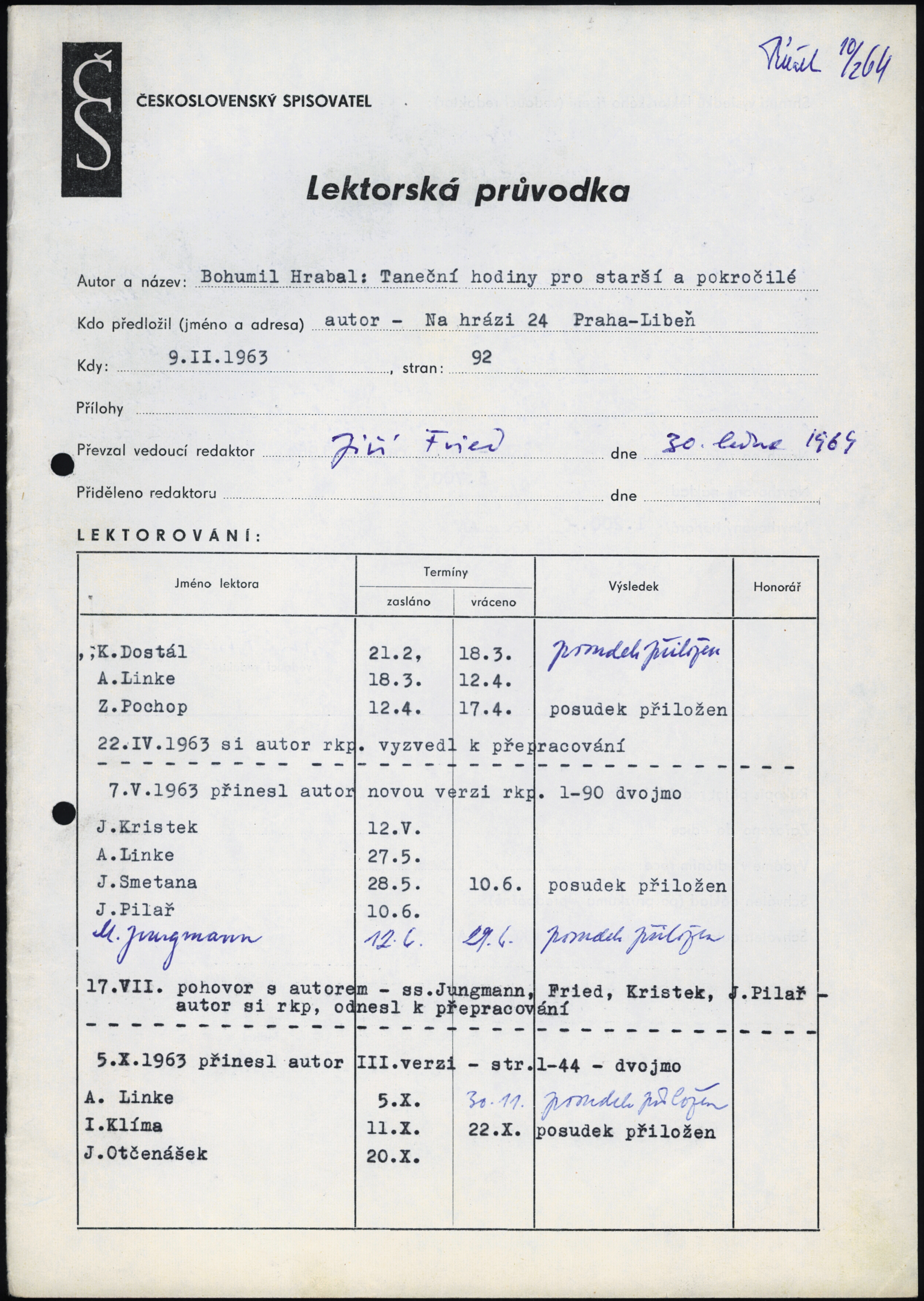

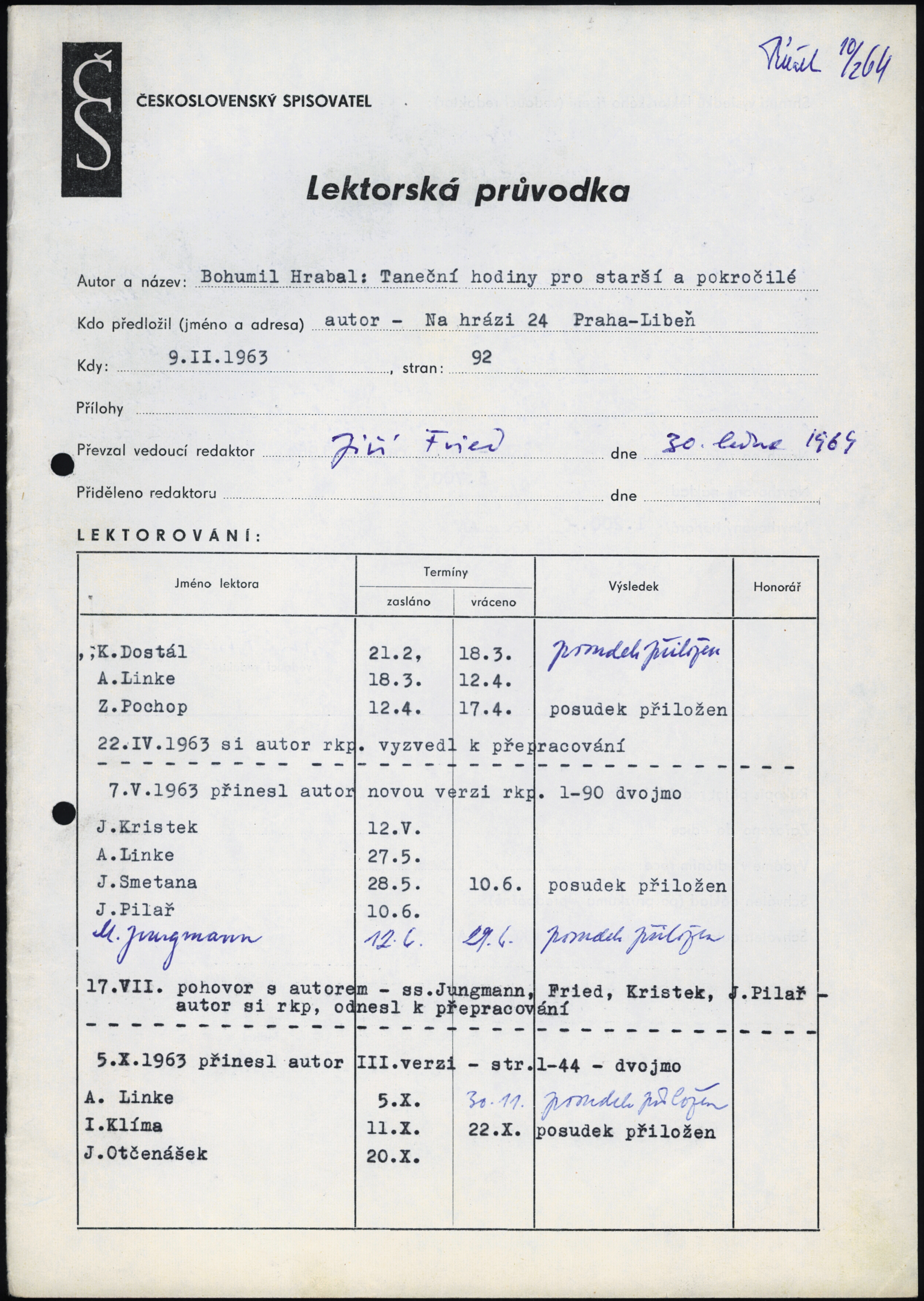

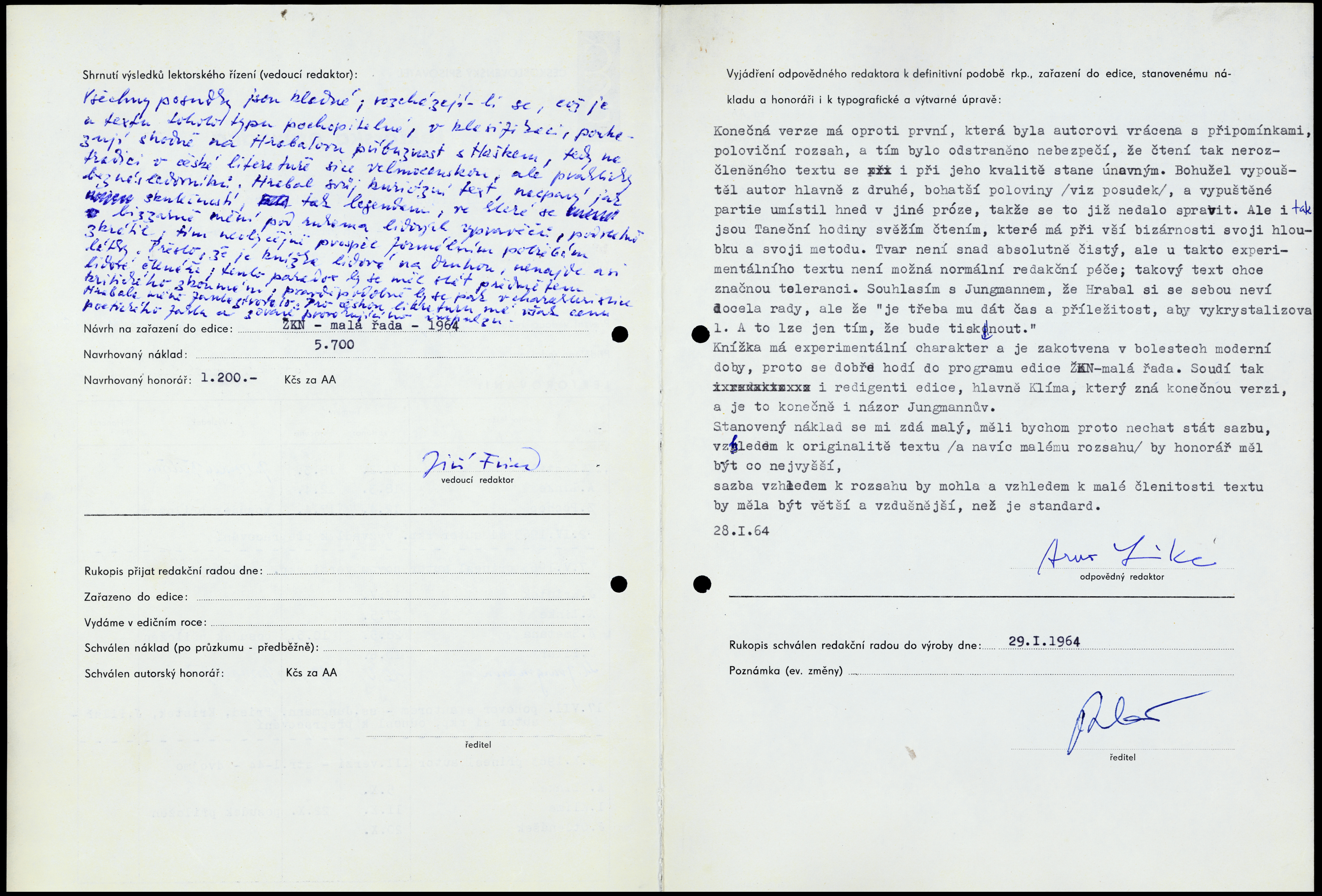

The Czechoslovak Writer Publishing House collection deposited in the Literary Archive of the Museum of Czech Literature (LA PNP) contains sources documenting the course of review processes, which often led to demands for changes to literary works. This was also the case for the experimental text entitled “Dancing lessons for the advanced in age” (1964) written by the well-known Czech writer Bohumil Hrabal (1914–1997). This text was finally shortened by the author following the reviewers’ requirements. “Dancing lessons for the advanced in age” consists of the only continuous and unfinished sentence representing the monologue of the seventy-year-old uncle Pepin who recalls his past. Other sources stored in the LA PNP documents include the prohibition of Hrabal's collection of short stories “Lark on a String”.

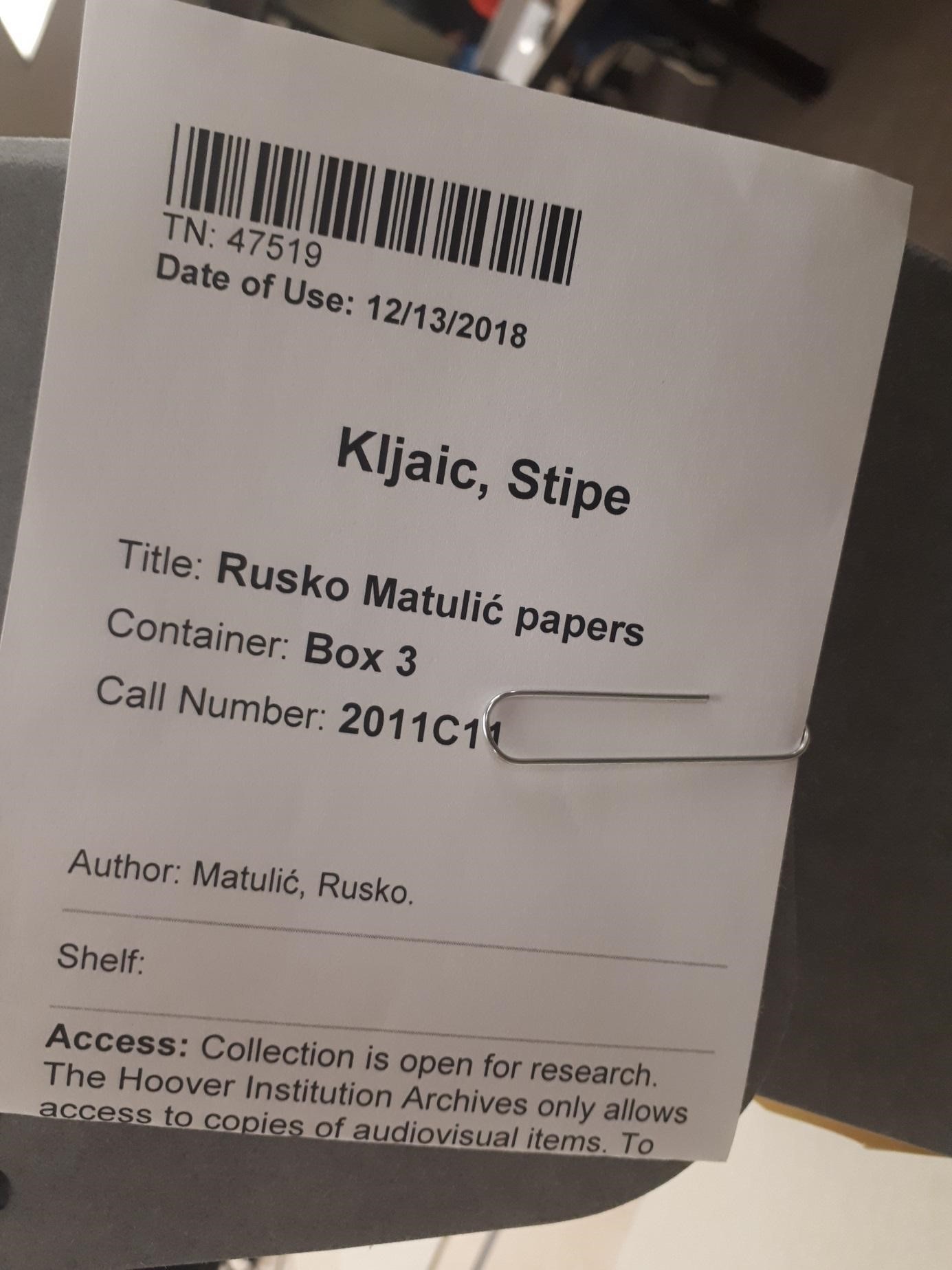

The bequest of Rusko Matulić, an American engineer and writer of Yugoslav origin, is held in the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. The collection largely encompasses Matulić's activities as a political émigré in the United States of America, when he mainly dealt with the publication of the bi-monthly bulletin of the Committee Aid to Democratic Dissidents in Yugoslavia (CADDY). The bulletin and organization acted as a part of the Democratic International, established in New York in 1979. Mihajlo Mihajlov, one of the most prominent Yugoslav dissidents, was a member and the main initiator of launching the CADDY organization and its bulletin. Rusko Matulić was Mihajlov's main collaborator in the overall CADDY project.

The collection illustrates Adrian Marino’s intellectual evolution as a historian and literary critic who chose to pursue his activity outside the institutions controlled by the communist regime. The Marino Collection includes books, original manuscripts, and the author’s correspondence, which reflects a critical perspective on Romanian literary life in the period 1964–1989.

Irimie, Cornel. Research on Pastoral Life in the Area of Mărginimea Sibiului, in Romanian,1964. File

Irimie, Cornel. Research on Pastoral Life in the Area of Mărginimea Sibiului, in Romanian,1964. File

From the 1960s to the 1980s, Cornel Irimie, together with museologists, ethnographers, and photographers working at the Brukenthal Museum in Sibiu, conducted ethnographic research on the civilisation of the Romanian villages that suffered as a result of forced collectivisation in the period 1949–62. This process dismantled the social structure of the Romanian village and produced great changes in the lifestyle of the peasantry (Kligman and Verdery 2011, 2). An exception to the rule were the shepherd villages that had been less or not at all affected by collectivisation. This is the case of villages in the area of Mărginimea Sibiului, at the foot of the Carpathian Mountains, west of the city of Sibiu.The research conducted by Irimie and his team in this area in the first half of the 1960s reveals the spiritual universe of shepherd communities in communist Romania. Its result was the German-language study “Neue Forschungen zum Hirtenwesen der Rumänen mit einer Darstellung der Mărginimea Sibiului als einer typischen Zone” (New Research on the Pastoral Life of Romanians with the Case Study of Mărginimea Sibiului as a Typical Area) written in December 1964. The study has twenty-nine typewritten pages and is divided into five chapters. The first chapter deals with the history of shepherding in the Romanian space and the biographical references on the topic, the second with the toponyms of shepherd villages in Mărginimea Sibiului and their origins, the third with forms of habitation in the shepherd villages of this area, the fourth with wool-processing techniques, and the fifth with religious beliefs and customs specific to shepherds. Within the latter topic, Irimie analyses the symbolism of the lamb within the religious universe of shepherds, and how this symbolism is present in customs during Easter celebrations. Research on certain religious practices from a sociological and ethnographic perspective, as in this study, was an activity that ran counter to the communist regime’s official policies. The authorities were always careful to describe religious practices in the Romanian rural world in negative terms, calling them reminiscences of rural backwardness.

![Lešaja, Ante. 2014. Praksis orijentacija, časopis Praxis i Korčulanska ljetna škola [građa] (Praksis Orientation, Journal Praxis and The Korčula Summer School [collection]). Beograd: Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung, p. 218.](/courage/file/n28836/Prvi+nastup.jpg)

The first public appearance of the entire editorial board of Praxis (Student Centre, Zagreb, end of 1964). From left to right: Rudi Supek, behind him (obscured from view), Branko Bošnjak, Gajo Petrović (editor-in-chief), Danilo Pejović (editor-in-chief), Predrag Vranicki, Milan Kangrga, Danko Grlić; far right (with back turned): the director of the Student Centre, M. Heremić, next to him, Antun Žvan.In the first issue of Praxis in 1964, the first core Praxis group, consisting of Zagreb-based humanist thinkers (philosophers and sociologists), proclaimed the basic platform of the future Praxis critical orientation. In his introduction entitled “Čemu Praxis?” (“Why Praxis?”) Praxis editor-in-chief Gajo Petrović announced the primary origin of the future Praxis orientation: “criticism of all that exists” (the phrase was taken from Karl Marx). This motto served as a principal starting point which generated a decade of criticism by Praxis thinkers; first of all philosophical and sociological analysis dealing with various topics and forms of “everything existing” in the sense of links between freedom and practice (the syntagma “all that exists” combined with criticism provides both an active and social meaning: the truth is verified in practice) This standpoint became the focal point for differentiation and promotion of the culture of dissent among Praxis thinkers and those supporting this orientation, but also among those who disputed it.Considering the promotion of the culture of dissent, which was in opposition to the concept of a single-party system, the editors of Praxis and the leaders of the Korčula Summer School were exposed to government attacks.The photograph, which was owned by Asja Petrović, is located in the Praxis and Korčula Summer School Collection. The photo is also published in the book written by Ante Lešaja (2014).

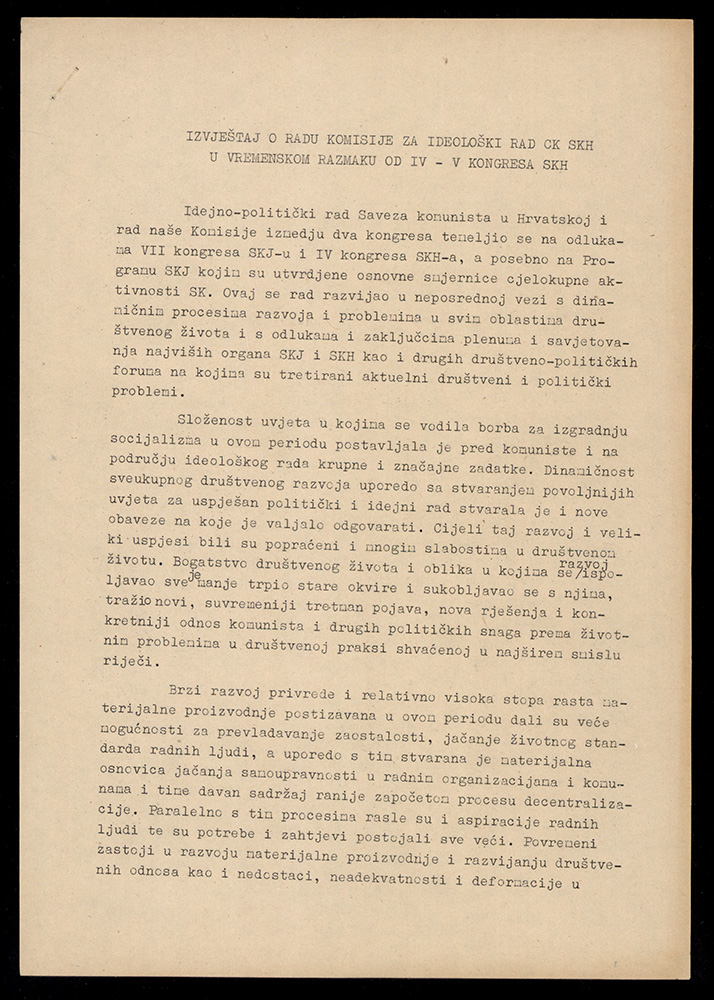

Report on the work of the Commission on Ideological Work of the CC LCC in the period from the 4th to 5th Congresses of the LCC, 1964

Report on the work of the Commission on Ideological Work of the CC LCC in the period from the 4th to 5th Congresses of the LCC, 1964

The report was dated October 1964, detailing the work of the Commission in the fields of culture, science and the media. It documents ongoing and systematic monitoring and the course of activities in the above-mentioned areas by the Commission through the practice of extended Commission meetings, discussions on prepared materials, as well as personal contacts by members and associates of the Commission with people from specific fields of cultural and scholarly life. In the report, we read numerous reviews and criticisms of cultural activities and the media. For example, the members of the Commission believed that Radio-Zagreb alone "managed to generate for one area the type of associates who will constantly and persistently fight for certain criteria, relationships, definitions and meanings of a specific art form from certain conceptual (clearly socialist) and aesthetic positions." Publishing was considered expensive, criticized for the low circulation of books and the neglect of the literature of Eastern countries, as well as the inadequate work of publishing councils. In film production, it was said that there were very rarely high-quality achievements: the greatest extent is achieved with cartoons of the Zagreb School of Animation, but other films "rarely use their range and conceptual profile to be active participants in performing social functions." The editorials of literary journals were criticized for the lack of understanding of social processes and development, the lack of Marxist criteria, and the presence of national overtones and romantic references to the past. However, the report says that conversations conducted in the Commission, for example with the people from the magazine Telegram, as well as other forms of influence at all levels and on different occasions, have shown that "it can speed up the process of conceptual cleansing with anarchic, pseudo-liberal, petit bourgeois and similar aberrations."