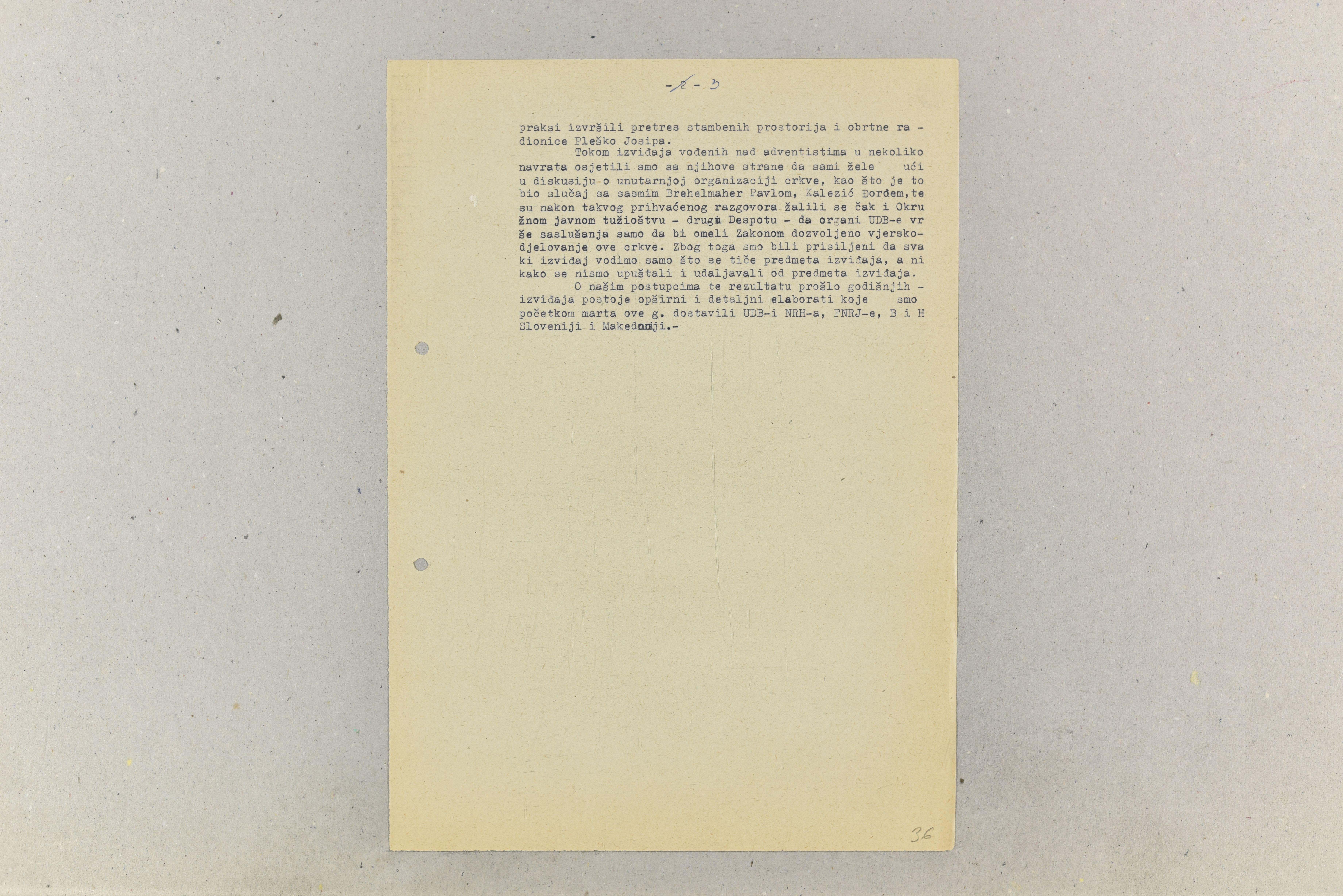

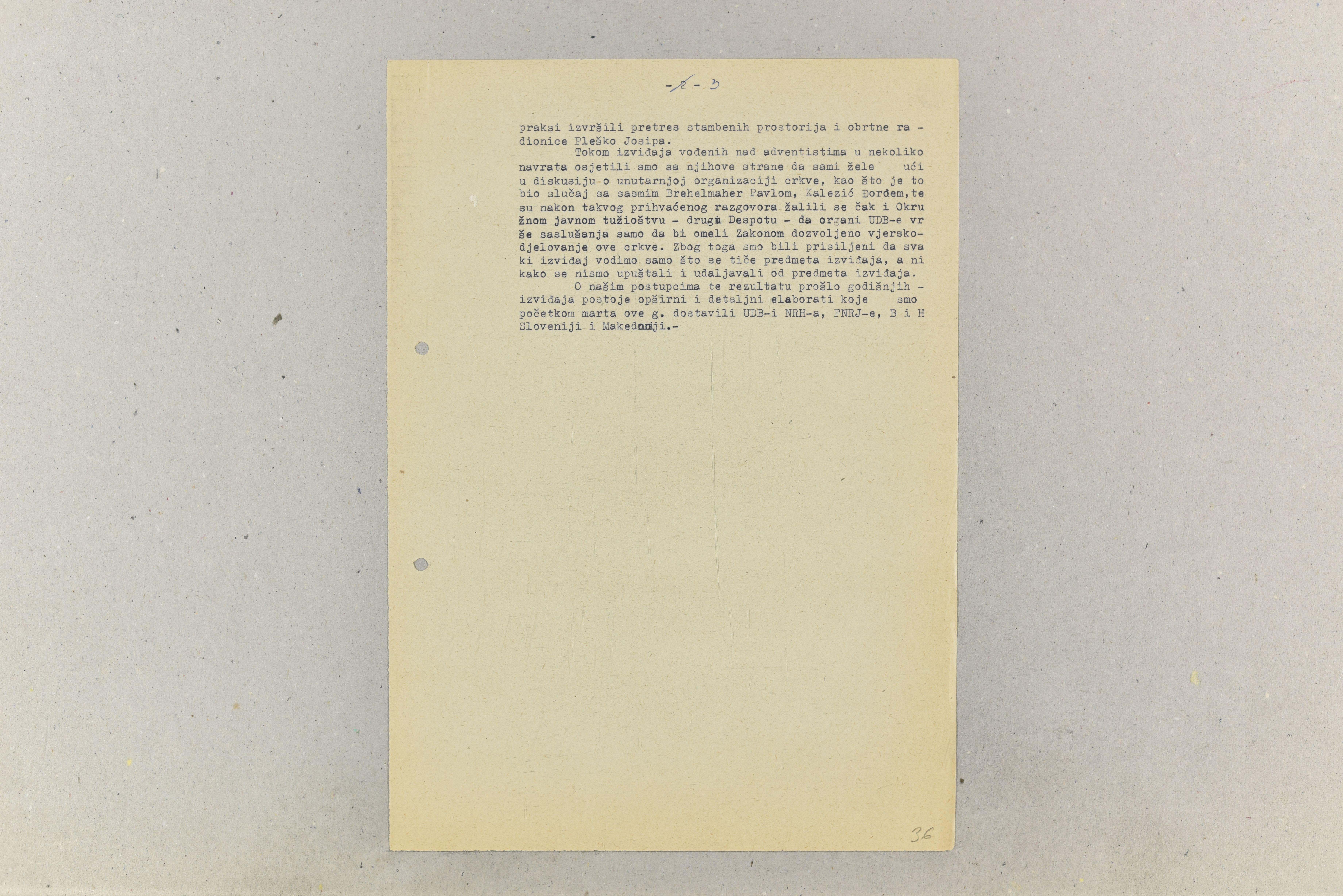

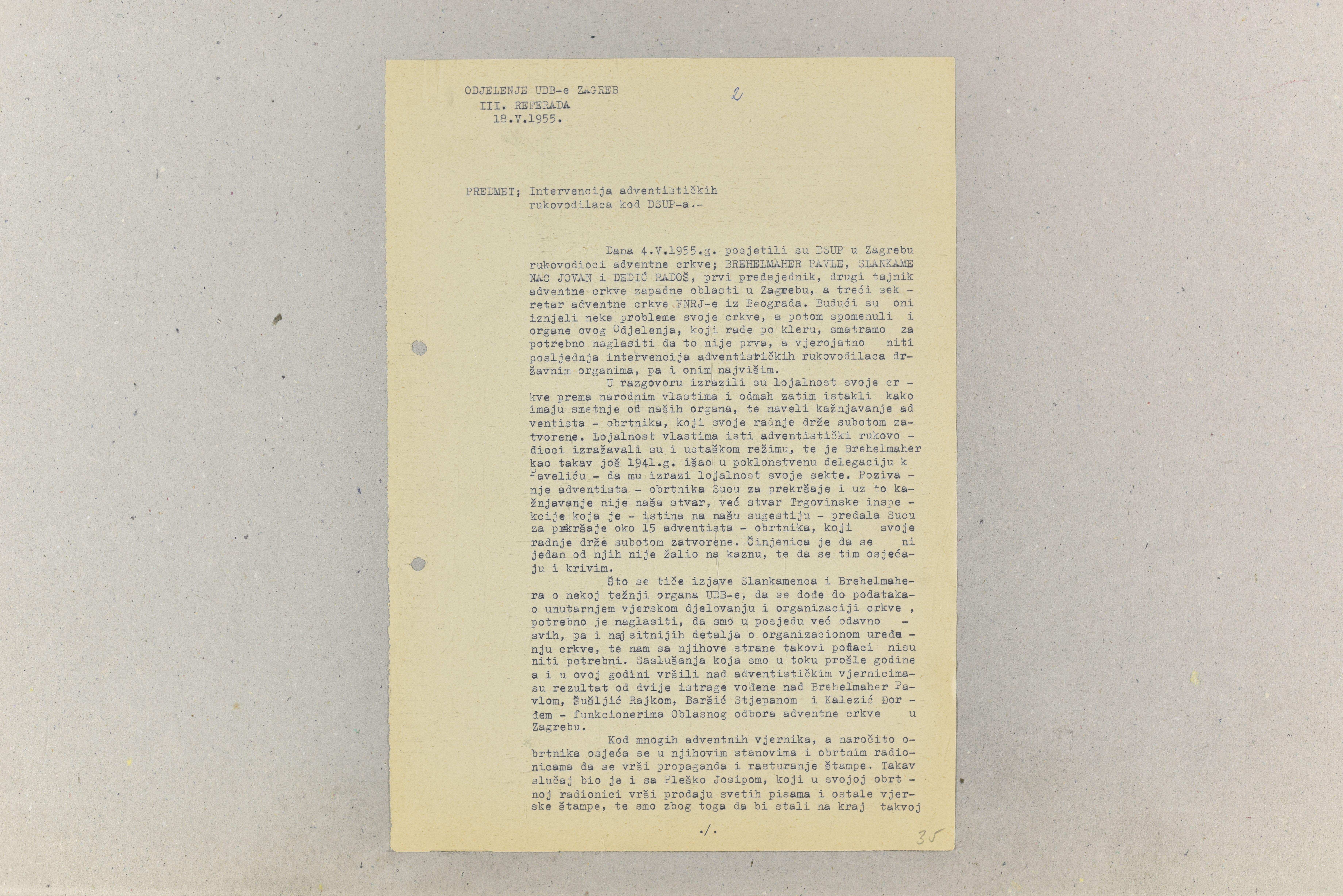

Information of the State Security Administration/Zagreb Department on a complaint from members of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, 1955. Archival document

Information of the State Security Administration/Zagreb Department on a complaint from members of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, 1955. Archival document

One of the religious communities whose activities were monitored by State Security Service was the Seventh-day Adventist Church, a Protestant denomination which has existed in the territory of Croatia since the beginning of the 20th century. Besides the problems common to all religious communities, problems in relations between the Seventh-day Adventist Church and the communist regime also arose, for instance, in education, employment and in the army due to absence from school and work on Saturdays on religious grounds. This is illustrated by an internal note by the State Security Administration/Zagreb Department dated May 1955, concerning a complaint from leaders of the Seventh-day Adventist Church to State Internal Affairs Secretariat of the People's Republic of Croatia.

The reason for the complaint was the initiation of infringement proceedings against 15 Adventist craftsmen, due to the closure of their workshops on Saturdays, filed by the State Security Administration/Zagreb Department. The note moreover reveals information on other State Security Administration activities related to members of the Seventh-day Adventist Church. It mentions the questioning of church members as a part of two investigations against leaders of the District Committee of the Seventh-day Adventist Church in Zagreb. Doubts were also expressed that many church members, in particular craftsmen, were “promoting and distributing” religious publications in their homes and workshops. To halt such practices, the State Security Administration conducted searches of their homes and workshops. Reports on the results of its investigations were sent by the Zagreb Department to the federal and republic State Security Administration, and to the equivalent services in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Slovenia and Macedonia. The extent to which the State Security Administration monitored the activities of religious communities is also illustrated by the following: in reply to a complaint from leaders of the Seventh-day Adventist Church to the State Internal Affairs Secretariat of the People's Republic of Croatia concerning the State Security Administration's intention to obtain data about the Church’s internal activities and organisation, the Zagreb Department stated that it “has long been in possession of all, including the minutest details, on the Church’s organisation.”

On the night of 18/19 May 1955, after suffering from verbal and physical abuse at the hands of two police officers at the Chişinău railway station, Zaharia Doncev produced four handwritten texts (leaflets) with a radical anti-regime message. He spread the four leaflets on the premises of the railway station and in the surrounding area. Doncev wrote the text on four white sheets of paper of notebook format, using a pencil. Three of the leaflets were in Russian, while the fourth was written in Romanian, in Latin script. The content of the Romanian-language and Russian-language texts was different. The Romanian text emphasised the crisis of the Soviet regime and appealed to the Moldavian people to rebel and show their “love” for Romania in order to regain their freedom:

“...as you can see, the Communists are getting themselves into a catastrophe. In a year, we will all be liberated. The time is ripe for each of us to take pitchforks and scythes in order to show that we love our dearest Romania that once was. The time has come for us to live better and more easily. Each of us must show his love for our former fatherland. This is the only way for us to win our freedom....”

The texts of the Russian-language leaflets were more explicitly anti-communist, more radical and more incisive in their criticism. One of them read as follows:

“Dear friends, very soon the whole Moldovan people will stand up for the interests that it had before the war. Communism is failing everywhere. Now they are going to find out how the poor Moldovan people lives. We have all become beggars; we have no bread, clothes or land. The time has come for us to rise and tell the communists: it is enough for you to get rich as flunkeys. The time is ripe for us to take revenge for this life of slaves. Each of us must do something to set us free from the communists. Let us prepare a powerful blow [for them]....”

The other two leaflets were less original, repeating the basic content of the one above. However, one of the texts also contained a direct reference to the “Jewish leadership” of the Communist Party, calling for “liberating our fatherland from communists and Yids [zhidov] who have climbed upon our backs” and were exploiting “all the people from the working class.” This passage is revealing for the persistence of anti-Semitic stereotypes within a part of the population and for the specific uses of the nationalist language originating from the interwar period to challenge the legitimacy of the Soviet regime. Although Doncev’s proclamations had no impact on a mass audience and were swiftly removed by vigilant policemen, they point to the patterns of the language of opposition that would emerge later. Besides the already mentioned interwar models of nationalist thought, another topic popular after 1945 was that of impending war with the West and the consequent “liberation” of Moldavia from Soviet domination. Despite the isolated nature of Doncev’s act of defiance, it was clearly indebted to broader patterns of anti-Soviet discourse that he probably borrowed from his earlier Romanian education, his family and his entourage. The context of the early Thaw is even more significant in order to understand Doncev’s motivations. The first signs of a more liberal approach to expressions of dissent, as well as the temporary weakening of police surveillance, provided a more favourable atmosphere for the voicing of discontent, which was to be confirmed by the impact of the Hungarian Revolution on the Soviet citizenry. By the time of Doncev’s arrest in December 1956, however, the party leadership and the KGB had moved decisively to reassert central control and crush any signs of open opposition to the regime. This also explains the harsh sentence in Doncev’s case, despite the overwhelming evidence that his actions had no impact on a wider audience. Still, the atmosphere of the Thaw played a role in the reduction of his prison term in 1960. In his appeal to the Soviet authorities, while emphasising his loyalty to the regime, Doncev also explicitly mentioned Khrushchev’s assertion during the Twenty-first Congress of the CPSU in 1959 that “we have no political criminals.” Although this was clearly intended to impress the recipients of his petition, it is significant that his case received a favourable resolution. The original versions of Doncev’s leaflets were not destroyed by the KGB operatives and are still part of his case file.

Decision of the Presidium of the Supreme Court of the Moldavian SSR Concerning the Case of Gheorghe Zgherea. 9 June 1955 (in Russian)

Decision of the Presidium of the Supreme Court of the Moldavian SSR Concerning the Case of Gheorghe Zgherea. 9 June 1955 (in Russian)

Almost two years after his condemnation, in the spring of 1955, Zgherea filed a petition addressed to the General Prosecutor of the Moldavian SSR, requesting the revision of his sentence. In this petition, Zgherea again admitted his guilt, but emphasised that his conversion to Inochentism was mainly caused by the influence of his parents. He claimed that, due to his young age and to the unsatisfactory level of his education, he did not fully understand the implications of his actions at the time. He also declared that, during his detention in the labour camp, he “fully realised the mistaken nature of his views” and therefore was ready to “cut all his ties to the sect of the Inochentists.” This remarkable example of repentance and apparently successful “re-education” should not be taken at face value, especially given the fact that during the trial Zgherea refused to abjure and renounce his faith. However, in the post-Stalinist Soviet context, this proved an effective strategy for alleviating his plight and for receiving a reduction of the sentence and, ultimately, a full amnesty. In his review of Zgherea’s case, one of the employees of the MSSR’s Ministry of Internal Affairs, Major Rogachev, noted the defendant’s partial admission of guilt and his apparent repentance as alleviating circumstances. In the Resolution he sent to the General Prosecutor of the MSSR, A. Kazanir, on 28 April 1955, Rogachev concluded that, although Zgherea’s “guilt” was not in doubt, the punishment was “too severe and did not correspond to the seriousness of his actions.” Therefore, Rogachev recommended that the prosecutor’s office file a formal protest to the Presidium of the Supreme Court of the MSSR in order to request a revision of Zgherea’s case, which the prosecutor did in due course. As a result of this protest, after reviewing the case, on 9 June 1955 the Supreme Court issued a special decision which reduced Zgherea’s sentence to five years of hard labour and a further three-year suspension of civil rights. The main argument of the court was that Zgherea “did not have a leading position within the sect.” This motivation points to a shift in the authorities’ perception of the social danger of the Inochentists and similar religious movements and to a more differentiated approach to the individual guilt of their members. Moreover, Zgherea was amnestied according to the provisions of the Decree of 27 March 1953, which ended the main wave of Stalinist repressions and secured a legal basis for the gradual release of political prisoners. He was to be released from the labour camp as soon as possible, while his penal conviction was dropped. This case certainly did not illustrate an entirely new attitude of the regime toward religious dissent, which continued to be viewed with suspicion and repressed. However, there was a marked shift in the authorities’ repressive strategies, which became subtler and more differentiated. The case of Gheorghe Zgherea is thus a fascinating example of essential ideological continuity uneasily combined with changing methods of addressing and dealing with dissent and opposition in the religious sphere.